Discovering

Father Con Scollen

1841-1902

Enjoy an article from Oblate Connections Ireland. The article among other things mentions Con Scollen’s great respect for Indian languages.

In Leon Doucet’s memoirs he speaks of Scollen:

Doucet relates, “I had to go to Saint-Paul-des-Cris and Brother Scollen, who spoke Cree very well, had to accompany the Cree of Bobtail and Ermineskin for some time, with Alexis as his companion.” 1 “1870: Fr. Lacombe is wintering at fort de la Montagne with Bro. Scollen and Alexis Cardinal to write his works in Cree: his dictionary, his sermons, etc. The fort de la Montagne was also called Fort Assiniboine.”2 Doucet states that in 1871-1872, “Fr. Lacombe was busy with his work in Cree and carefully taught this beautiful language to his two young companions (Doucet and Scollen). It was a monotonous life for a father who was used to an active life almost always travelling, but he was compelled by devotion to carry on the work for the benefit of the young missionaries.” 3 “Fr. Lacombe helped us to make great progress in our study of Cree and each Sunday after Mass, he would correct our short essays (lessons) in this language which we would create to the best of our ability; we learned them by heart.”4 ‘Brother Scollen was to be his interpreter because he, Mgr. (Grandin) spoke Cree with difficulty.” 5

- The Journal and Memoir of Fr. Leon Doucet OMI 1868-1890: 46

- The Journal and Memoir of Fr. Leon Doucet OMI 1868-1890: 36

- The Journal and Memoir of Fr. Leon Doucet OMI 1868-1890: 48

- The Journal and Memoir of Fr. Leon Doucet OMI 1868-1890: 49

– Ken Forster, OMI

_____________________________________________

In this article Fr. Mike Hughes helps introduce us to the story of Fr. Con Scollen. This brief introduction draws on an increasing number of sources such as writings by Ian Fletcher, Harry Winter and Johnathon Ryan all of which tell us of the renewed interest in the story of this Oblate missionary. So who was he?

His mother died in the Great Famine in Ireland. His family emigrated to the coalmining area of Durham in the north of England and he went on to become an Oblate lay brother, living among the Blackfoot, Cree and Métis peoples on the Canadian Prairies and in northern Montana in the United States. He made a significant contribution to the study of the First Nation

His mother died in the Great Famine in Ireland. His family emigrated to the coalmining area of Durham in the north of England and he went on to become an Oblate lay brother, living among the Blackfoot, Cree and Métis peoples on the Canadian Prairies and in northern Montana in the United States. He made a significant contribution to the study of the First Nation

languages, and much more…. Yet he is little known among us.

He followed two of his friends and joined the Oblates in Sicklinghall, near Leeds in Yorkshire, on 14 August 1860. A momentous opportunity came to go with Oblate Archbishop Taché of St. Boniface to Canada. Con wrote: “For a long time I have prayed to my dear Mother Mary, that She would grant me an opportunity of going to the Foreign Missions. When Doctor Taché came here, I thought my prayer was granted. So accordingly I asked him to take me with him to North America”.

So the great adventure of his life started! “Scollen travelled to Fort Edmonton where, as a lay brother, he was immediately assigned the task of opening a school. He became devoted to his work and was praised by his superiors for his efforts. ‘The more I teach these poor little children’, he wrote, ‘the greater love I feel for them and the greater is my desire to see them advance rapidly in their studies. My pupils are 30 in number.'”

What kind of a missionary was he? “Johnathon Ryan during his long interview in 2017 with Marvin Yellowbird, one of the Samson Cree chiefs, was urged by Yellowbird to learn about Scollen as a model of positive influence by the white man. Scollen ‘displayed no interest in converting them into ‘good subjects of the Crown,’ as he would say sarcastically in many of his letters. Scollen saw exactly what that meant in his native Ireland.”

What kind of a missionary was he? “Johnathon Ryan during his long interview in 2017 with Marvin Yellowbird, one of the Samson Cree chiefs, was urged by Yellowbird to learn about Scollen as a model of positive influence by the white man. Scollen ‘displayed no interest in converting them into ‘good subjects of the Crown,’ as he would say sarcastically in many of his letters. Scollen saw exactly what that meant in his native Ireland.”

His main biographer, Ian Fletcher, states “he had an extraordinary talent for languages and became the foremost linguist in the Oblates in Canada” Con plunged into the study of the Cree and other Indian languages: I said I had to learn the Indian languages in order to instruct the Indians. The missionary who attempts to convert Indians through an interpreter or

by trying to teach them his language, or by spreading bibles and pamphlets broad-cast among them, as I have known some evangelical societies to do, is simply losing his time, and is guilty of an imposition.

His first years on the mission were as a lay brother. For the sake of his mission he was ordained in 1873. Throughout his ministry he was by the side of his people. During the mid-1870s, he saw the plight of the First

Nations people of Alberta. He watched the bison disappear, hunted to near-extinction by those pouring into the West. Knowing how much the Plains tribes depended on the animal for their food, Scollen believed

starvation was a real possibility for his friends.

“History is the complicated story of the human race, and often we try to make it fit narrative we force on the world. Usually it’s because we want to make ourselves look better than our ancestors”

This realization helped him agree to aid the Canadian government as it sought to make treaties with the First Nations tribes. After the treaties were signed, however, the tribes were sent to reservations. When Scollen

visited each reserve, he saw the Canadian government wasn’t keeping its promises. The Indian agents often refused to let the tribes farm or take other steps to improve their situations.

Rumors were circulated that Con was drinking and acting erratically. His enemies among the Canadian officials wrote to Bishop Vital J. Grandin of St. Albert and to Oblate leaders to accuse him of “gross immorality with Indian women.” The outcry prompted Grandin to recall Scollen for an investigation into his activities. But Scollen was difficult to locate; he was

eventually discovered among the Blackfoot tribe in Montana, ministering to them while they hunted bison. After a lengthy investigation, the bishop absolved Scollen of all charges.

Conditions among the Cree were getting progressively worse. The government-appointed Indian agent of the Bear Hill Cree ruled them with an iron fist. Eight chiefs approached Scollen to write a letter for them to

the Edmonton Bulletin to beg for help — a letter that was published February 3, 1883, reading in part:

We are reduced to the lowest stage of poverty. We were once a proud and independent people and now we are mendicants at the door of every white man in the country; and were it not for the charity of the

white settlers who are not bound by treaty to help us, we should all die on government fare. Our widows and old people are getting the barest pittance, just enough to keep body and soul together, and there have been cases in which body and soul have refused to stay together on such allowances. Our young women are reduced by starvation to become prostitutes to the white man for a living, a thing unheard of before, amongst ourselves and always punishable by Indian law. What then are we to do? Shall we not be listened to?

The Canadian government responded to Scollen’s defiance with abuse and threats. William Anderson, the Crown’s Indian Agent, wrote to Bishop Grandin, asking him to “compel the Reverend Mr. Scollen to cease making trouble among the Indians or leave this District or that I should be compelled to have him arrested.” The bishop, for his part, refused to have

Scollen removed. Instead, the pair continued to appeal to the Canadian government to fix the problem.

Scollen’s position on his First Nation friends showed the prophetic nature of his insights:

First and foremost, I wish the reader to bear in mind that the Indian is the only real American on this continent. We hear a great deal every day about foreigners, &c., coming to America. The first is, all white men and all black men throughout this whole American commonwealth, are comparatively nothing but foreigners. The pure Indian, the unmixed red man, and he alone, is the native, the aboriginal American. All others are either Europeans, Asiatics or Africans, and have been transplanted to this American soil… The red man, and he alone, is the native child and primitive possessor thereof the land.

Scollen wrote these lines in 1893 to newspaper readers who would have scorned his views. Not only was he recognizing Indians as fellow human beings, he also affirmed their claim to the land. Although he did want the First Nations people to be Catholics, he didn’t want them to eradicate their culture. Scollen’s respect for those he ministered to shows through clearly in the essential element he chose that would preserve Native American

culture in the coming generations: their languages.

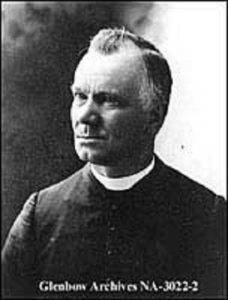

Today a variety of sources are reviving his memory. Fortunately a Canadian archive holds a treasure trove of correspondence which can be consulted on-line. We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of the

Glenbow Archive. While the book ‘Thirty Years among the Indians of the Northwest. The personal experiences of Father Constantine Scollen’, edited by Ian M. Wilson, is available on Kindle.

In this dip into a highly complex subject we have drawn on freely on these and other sources and recommend them to our readers who wish to go deeper. As Jonathon Ryan notes, “History is the complicated story of the human race, and often we try to make it fit the narrative we force on the world. Usually it’s because we want to make ourselves look better than our ancestors. And we mumble half-thought-out apologies for the past without really reflecting on the needs of the present, thinking that will somehow fix everything. In truth, history is complex because humans are complex.” (The residential schools were instituted by the Canadian

government in conjunction with Protestant denominations and the Catholic Church during the 19th and 20th centuries) The Catholic Church in Canada operated some of the residential schools but also fought hard against the Canadian government for First Nations rights. We want our stories neat and tidy, with the good and bad guys clearly defined. But, often, they can be the very same person, and it might be us.”

From the Archives

Published in Oblate Connections