Doctrine of Discovery stands in reconciliation’s path

Pictured left: First landing of Columbus on the Shores of the New World by Dioscoro Puebla.

It should be no surprise that the Age of Discovery would have produced a Doctrine of Discovery. How uncomfortably that doctrine sits in our history now presents the Church and Canadians with a further obstacle to reconciliation.

“I am asking the Holy Father to renounce and formally revoke the 1493 Doctrine of Discovery and replace it with a new papal bull that decrees Indigenous peoples and cultures are valuable, worthy and must be treated with dignity and respect,” Assembly of First Nations National Chief RoseAnne Archibald told The Catholic Register in an email before 13 AFN delegates were scheduled to meet with Pope Francis in Rome in December, a meeting since rescheduled for March 27 to April 1.

The request that the Church reverse its Renaissance-era doctrine is not new. Indigenous scholars and nations have been talking about the effects of this doctrine and the legal concept of terra nullius for the last half century, at least. There is no chance it won’t come up in the conversations Inuit, Metis and First Nations delegations will have with Pope Francis in Rome.

“We’ve been asking to seek justice for our people. We’ve been asking to have the governments recognize us as the first people. We’ve been asking for reconciliation and we start with the Doctrine of Discovery,” Dene Chief Norman Yakeleya told reporters on a nationwide Zoom call in the days before the original meeting was postponed due to rising COVID-19 numbers. “We’ve got to go back to the source of how we’ve been treated in Canada by all the institutions.”

Yakeleya heads up the residential school file for the AFN and will lead his delegation in Rome.

The Doctrine of Discovery established the rules for European conquest and colonization. It gave properly commissioned European explorers the right to claim lands not inhabited by Christians for their Christian kings and queens. There may have been people living there, but if they weren’t Christians the land was considered terra nullius — empty land belonging to no one.

The 2008 to 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission recognized the importance of the Doctrine of Discovery to any process of reconciliation. Its Call to Action #49 said, “We call upon all religious denominations and faith groups who have not already done so to repudiate concepts used to justify European sovereignty over Indigenous lands and peoples, such as the Doctrine of Discovery and terra nullius.”

Historial Origins

Although the 1493 papal bull Inter Caetera, issued by Pope Alexander VI, is often identified as the origin of the Doctrine of Discovery, it actually has a longer and more complicated history than any single papal decree or statement. It goes as far back as the middle of the 13th century, when Pope Innocent IV, as Christendom was threatened by Mongol hordes to the East, declared that killing and enslaving non-Christians was not acceptable, unless the non-Christians actively opposed preaching of the Gospel.

In 1344 Pope Clement VI issued Tuae devotionis sinceritas, a bull granting the Canary Islands to Luis de la Cerda and his heirs, along with the title of “Prince of Fortuna.” This established a precedent for automatic European sovereignty over newly discovered lands and people.

De la Cerda and his heirs were basically gangsters in sailboats and by 1434 Pope Eugene IV had rethought his predecessor’s magnanimity in creating a Prince of Fortuna. In Creator Omnium, Pope Eugene forbade further raids and freed the slaves of the Canary Islands. The next year, he doubled down with a penalty of excommunication on any who enslaved Canary Island natives who were Christian.

Perhaps the most brutal expression of this idea that new lands and the non-Christians who lived in them were beyond Christian charity came in Pope Nicholas V’s bull Romanus Pontifex, which gave Portuguese King Alfonso license to “invade, search out, capture, vanquish and subdue” people in the lands of discovery. The king was instructed to “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to apply and appropriate to himself and his successors their kingdoms, dukedoms, countries, principalities, dominions, possessions and goods, and to convert them to his and their use and profit.”

But the 1493 bull is the big one, because its effects were so far-reaching. The bull was intended to put an end to the threat of war between the Spanish and Portuguese. The kings of Castile and Leon were granted the right to establish dominions in most of the Americas — everything west of a line from the North Pole to the South drawn 100 leagues west of the Azores and Cabo Verde. This line, agreed to in the Treaty of Tordesillas, is the reason people in Brazil speak Portuguese and people in Mexico and Argentina speak Spanish.

Early Opposition

But while this was going on, a couple of Dominicans were pushing Church teaching in a very different direction. Antonio de Montesinos saw the effects of this doctrine in the evils of slavery on the Island of Hispanola (home to Haiti and the Dominican Republic). On the fourth Sunday of Advent, 1511 he preached:

“Tell me, by what right of justice do you hold these Indians in such a cruel and horrible servitude? On what authority have you waged such detestable wars against these people who dwelt quietly and peacefully on their own lands? Wars infinite number of them by homicides and slaughters never heard of before. Why do you keep them so oppressed and exhausted, without giving them enough to eat or curing them of the sicknesses they incur from the excessive labour you give them, and they die, or rather you kill them, in order to extract and acquire gold every day.”

We know that’s what he preached because a brother Dominican, Bartolome de las Casas, wrote it down. De las Casas went on to become bishop of Chiapas in Mexico and the father of the very idea of human rights.

In 1537 Pope Paul III wrote that Indigenous people are, in fact, “truly men.” Recognizing their humanity was, for the pope, a precondition for evangelizing and baptizing them. However, this bull, Sublimus Dei, was never promulgated. Which doesn’t mean that it wasn’t the teaching of the Church, only that the kings and queens of the 16th century were disinclined to follow the pope’s advice. A year later Paul III reiterated his teaching in a papal brief called Pastoral Officium, which excommunicated anyone who enslaved Indigneous people of the Americas or stole their land.

But the Doctrine of Discovery lived on, despite Pope Paul III’s opposition.

Legal Implications

Arguing that the Church is not responsible, or no longer responsible, for the Doctrine of Discovery because there were countervailing movements in early modern theology and even in papal statements does nothing to advance reconciliation, argues Anglican National Indigenous Archbishop Mark MacDonald.

“The title ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ has become the symbol, catchphrase and summary of an embedded, complex and multifaceted web of ideas, practices and cultural, legal, political structures,” said MacDonald. “It appears to describe, if not the beginning and ongoing vitality of the oppressive colonial system, its centre. Insistence that it has been undone by later pronouncements, something I understand and agree with, misses the point.”

University of St. Michael’s College medievalist and historian Giulio Silano points out that “The doctrine of discovery is a legal doctrine, not a dogmatic one.” Because of its legal nature it easily slipped from papal bulls into secular, legal codes.

On Canada’s behalf, the Protestant British Empire embraced this Catholic legal principle in the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This proclamation is often praised for recognizing the right of Indigenous people to inhabit their traditional lands. But at the same time, it gave the legal title for those lands to the Crown.

Established by radical, breakaway Protestants and officially secular in its constitution, the United States also embraced the Doctrine of Discovery. As Secretary of State in 1792, Thomas Jefferson declared the doctrine international law and foundational to the new government of the United States.

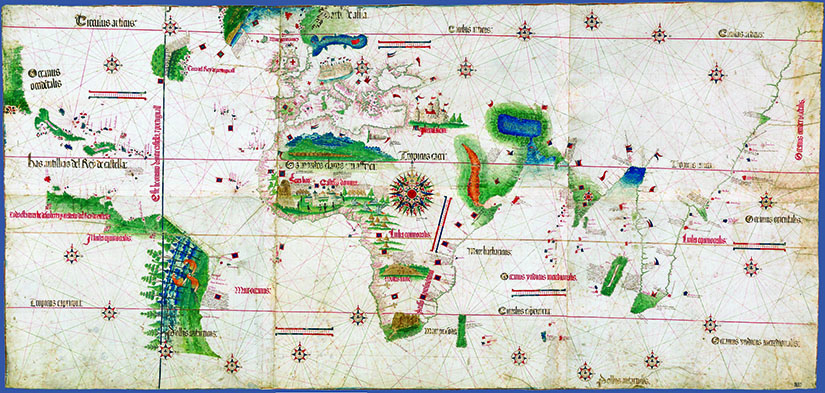

The 1502 Cantino map outlines how Pope Julius divided up the non-Christian world at the beginning of the Age of Discovery (Photo from Wikimedia)

Since the Second Vatican Council, the very heart and soul of Catholic teaching has been turned against the Doctrine of Discovery and all that it implies. The Council fathers put the Church clearly on the side of freedom, dignity and human rights.

“There must be made available to all everything necessary for leading a life truly human, such as food, clothing and shelter; the right to choose a state of life freely and to found a family, the right to education, to employment, to a good reputation, to respect, to appropriate information, to activity in accord with the upright norm of one’s own conscience, to protection of privacy and rightful freedom even in matters religious,” Council fathers wrote in Gaudium et Spes, the Church’s pastoral constitution.

In Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, on the 500th anniversary of Christopher Columbus running his ships into Hispaniola, Pope John Paul II made it abundantly clear that this teaching applies to the Indigenous people of the Americas. He begged forgiveness for the sins of the Church committed throughout the Spanish conquest. In his homily the pope said the anniversary should be the occasion to “seek pardon for offences and create the conditions for the just development of all, especially those most abandoned.”

Modern Papal Opposition

At Fort Simpson in 1987, Pope St. John Paul II invoked Pope Paul III’s brief Pastoral Officium as he laid out Church teaching for Indigenous people.

“The Church extols the equal human dignity of all peoples and defends their right to uphold their own cultural character with its distinct traditions and customs… He (Pope Paul III) affirmed their (Indigenous people’s) dignity, defended their freedom and asserted that they could not be enslaved or deprived of their goods or ownership. That has always been the Church’s position,” he said.

In 2000, kneeling before the Holy Doors as he opened the Great Jubilee, John Paul II begged forgiveness for the times the Church had relied on violence in its efforts to evangelize.

“John Paul II’s statements on Indigenous rights were inspiring to me and I wish that more Roman Catholics (especially most of the Canadian bishops) were familiar with them,” MacDonald said. “I personally do not feel that repudiation (of the Doctrine of Discovery) is necessary. What is critical is the apology.”

In 2007 Pope Benedict XVI acknowledged “the shadows that accompanied the evangelization of the Latin American continent,” while in 2015 at Santa Cruz in Bolivia, Pope Francis asked forgiveness for sins, offences and crimes committed by the Catholic Church against Indigenous peoples during the colonial era.

Could Pope Francis issue a new bull? Since Pope Leo XIII opened the era of papal encyclicals with Rerum Novarum in 1891, not many papal documents have been called bulls. But the term merely means any papal letter issued “sub bulla,” points out Silano. Its solemn papal seal is what makes it a bull.

By Michael Swan

Published on The Catholic Register website