Hollow core

Pictured left: The rainbow sheen of an oil spill is visible in the Huayuri creek in Peru, which lies within Block 192, a plot of land in the country’s Amazon rainforest. (Photography by Patrick Murayari)

In 2018, Ottawa announced a new watchdog to probe alleged abuses by multinationals. It has yet to complete a single investigation. The Globe went to Peruvian oil country to see the effects of missing Canadian oversight

Deep in the rain forest of Peru’s northern Amazon region, Natanael Sandi picks up a stick and pokes creek water that has an iridescent sheen. Nearby, oil clusters near a corroded pipe.

That petroleum seeps into the forest ground and creek beds, and oozes into the very rivers, streams and lagoons that Indigenous communities in the area – including the Quechua, Achuar and Kichwa peoples – use to bathe, wash clothes, grow crops and drink from. They also consume the fish and wild game that subsist on these waterways.

“The water that we drink, the air that we breathe – it is not normal, natural air. There is so much contamination in our territory,” says Mr. Sandi, 37, an Achuar father of four.

As an environmental monitor for the village of Jose Olaya, Mr. Sandi is responsible for tracking and reporting oil contamination for an Indigenous federation that then notifies environmental authorities.

As part of the world’s largest rain forest, the region he lives in – located more than 1,000 kilometres from the capital city of Lima – is environmentally crucial, and home to thousands of Indigenous peoples. It’s also a region blighted with pollution.

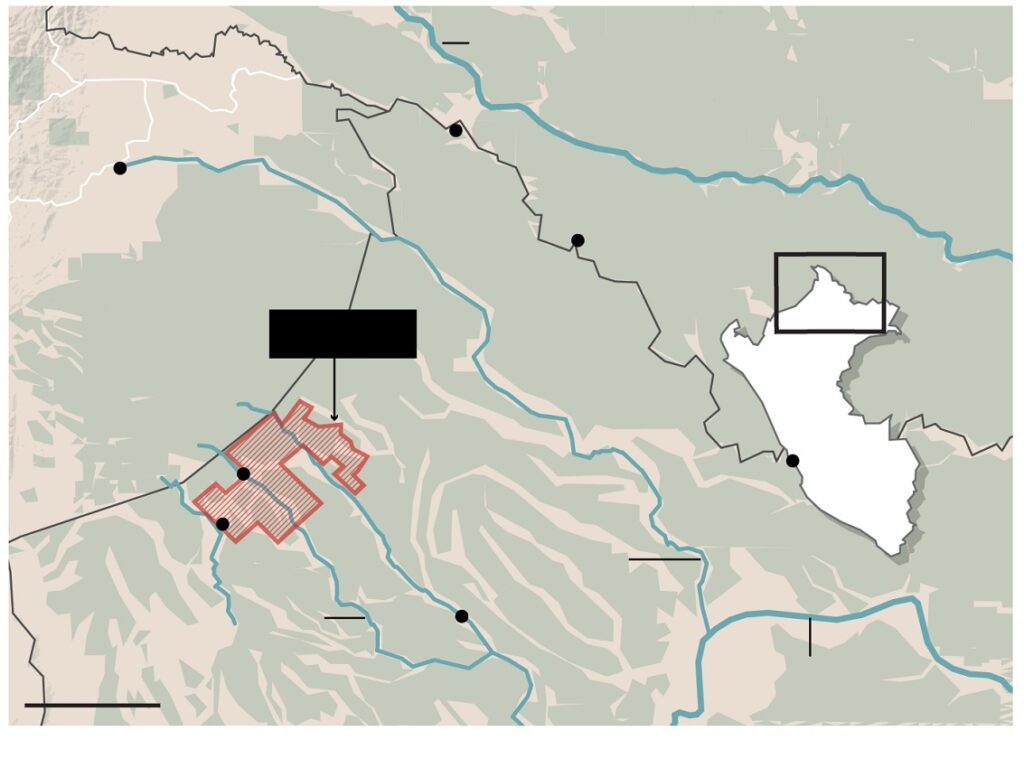

Oil spills and leaks from aging pipelines, wells and infrastructure have persisted here for decades. Mr. Sandi’s territory is in Block 192, a plot of land nearly equivalent in total area to that of Prince Edward Island. Oxfam, the international organization that fights global poverty, has called the block “one of the worst environmental disasters you’ve probably never heard of.”

Foreign companies, first from the U.S., and then Argentina, have extracted oil in the block since the early 1970s. In 2015, Peru awarded operations of the area to Canadian hands: Calgary-based Frontera Energy Corp., a mid-sized explorer and producer of oil and natural gas, whose service contract expired in February, 2021. (The lot has been dormant since).

Environmental emergencies in Block 192 have not been uncommon over the decades, but during Frontera’s time in the area, Peru’s environmental regulator recorded 113 of them.

Although it can be difficult to know when specific oil contamination occurred, the oily water Mr. Sandi brought The Globe and Mail to is a few minutes’ drive from a facility formerly used by Frontera. He escorted The Globe to several other such sites at the end of last year.

Frontera, which is listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, has earmarked money toward remediating the area. But Mr. Sandi and others in these territories say the efforts have been insufficient, and are calling upon the Canadian government to hold companies to account – something it had pledged to do.

In 2018, the government announced that it would create the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise, an office it said would have robust powers to demand answers and shame laggard companies operating abroad.

Canada is home to an outsized number of companies in the extractive sector – including nearly half of the world’s publicly listed mining companies – and the CORE was touted by the Liberals as a watchdog befitting of the country’s standing in the global economy. But despite promises that the office would be given investigatory powers – such as the ability to compel the production of documents – that never happened.

For that reason, Indigenous leaders in Peru’s Amazon decided not to pursue a complaint with the office. And in its four years in operation, The Globe found that the CORE, which has an annual budget of $4.9-million, has yet to complete a single investigation.

In addition to lacking meaningful powers, the original intention to expand the CORE’s mandate beyond the mining, oil and gas, and garment sectors has been unfulfilled – even while evidence exists that industries outside of its remit deserve probing.

There is no shortage of alleged human-rights abuses – including harm done to people and the environment – that Canadian authorities could investigate. The Globe has recorded more than 50 instances in 30 countries in the last five years alone, based on media reports, NGOs, academic reports and legal documents. The majority involve the mining sector, but they are also in the oil and gas, manufacturing and apparel industries.

The allegations, from workers, local villagers, community leaders and organizations against Canadian companies, in many cases are grave: killings of Indigenous community members; security forces opening fire on protesters; death threats against local leaders; health impacts from contaminated water; forced labour; and dangerous working conditions.

Ketty Nivyabandi of Amnesty International Canada says the group is ‘very disappointed’ with the current state of the Canadian Ombudsperson for Responsible Enterprise. (Blair Gable/The Globe and Mail)

But as a result of the CORE’s inadequacies, many of the human-rights groups that clamoured for the creation of such a watchdog have turned their backs on the project entirely.

“We’re very disappointed right now. This is not what we had advocated for,” said Ketty Nivyabandi, secretary-general of Amnesty International Canada, a human-rights group that had been supportive of the vision for the initiative. “We’re not recommending the office to communities that we engage with.”

When parliamentarians held hearings in 2021 to consider the CORE’s mandate, in response to criticism about its effectiveness, it heard testimony from Aymara Leon Cepeda, an official from Puinamudt, an umbrella organization for various Indigenous groups of the Amazon.

She specifically called out Frontera for not responding swiftly to spills and lamented the fact that the CORE – which she said had a “lack of power” – wasn’t an office worth approaching to address that inaction.

In light of Ms. Cepeda’s public testimony, The Globe requested an interview with the CORE’s staff half a dozen times over several months, but no one was made available. E-mailed questions were often answered unsigned, with direction to visit their website for information about the office.

Struck by the gravity of Ms. Cepeda’s criticisms, The Globe set out to Peru’s Amazon to find out what, if anything, the CORE was missing.

By Tavia Grant

Photography by Patrick Murayari

Published on The Globe and Mail website