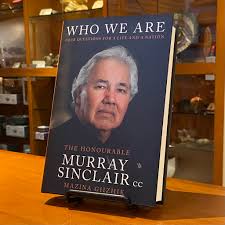

Murray Sinclair Questions Who We Canadians Are

Book Review

The Honourable Murray Sinclair’s memoir, Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation, offers a profound reflection on identity, justice, and reconciliation in Canada. As a lawyer, judge, and Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Sinclair played a pivotal role in shaping the national conversation on Indigenous rights. In this review, Joe Gunn explores the key themes of Sinclair’s life and legacy, highlighting the wisdom and challenges he leaves for all Canadians.

Who would have thought that one of the most accomplished Canadians of our era thought of himself as The Ugly Duckling? And not because of his looks! In the fable recounted by Hans Christian Andersen, even a swan born into a group of ducklings could be seen to be less worthy – until some new consciousness emerged.

The Honourable Murray Sinclair left an indelible mark on Canadian society. Although he died in November 2024 at 73 years of age, he has, very fortunately for us, left a memoir worth treasuring.

A lawyer, Murray Sinclair became Manitoba’s first Indigenous judge in 1988, co-led the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry in that province, and was best known nationally as the Chief Commissioner of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) for Canada from 2009 – 2015. He was later appointed to the Senate, was awarded the Order of Canada in 2022, and was the recipient of 20 honorary degrees.

Born in the former St. Peter’s Indian Reserve along the shores of the Red River, Sinclair’s mother died of a stroke a year after his birth. He and his three siblings were raised by their grandparents. The family was eventually forced to move to the Peguis First Nation near Selkirk, MB. There, in high school, Sinclair excelled at academics and sports.

Throughout his childhood, young Murray fervently practiced the Catholic faith. He was constantly made aware that his grandmother desired that he become a priest. She had grown up at a residential school and worked in the nuns’ kitchens. Although deeply disappointed when he declined to go to seminary, Sinclair’s devotion to her was so strong that he left university to care for her when she later fell ill.

Returning to studies was not easy. Among the 20,000 University of Manitoba students at that time, there were no Indigenous professors and perhaps only 15 Indigenous students. As Sinclair recounted, “There’s nothing quite as lonely as feeling like you’re the only person in the room, even though the room is full.” (page 91) At that time, racist prejudices against Indigenous viewpoints and realities were rampant in city, in curricula and on campus.

Most famous for his leadership of the Commission into Indian Residential Schools (IRS), Sinclair’s memoir recounts the personal cost of doing this work. Perhaps his own family history helped him patiently listen and hear the hours of testimony of IRS survivors. Sinclair recounts that his grandmother “taught me the importance of listening, and not just listening as in hearing but also in making a true effort to understand…” (page 174.) He had discovered his own father had been sexually abused by a priest at the Ft. Alexander school, causing his grandparents to opt out of status and move away from the reserve community at Saugeen. And his older brother was murdered while in the military – those responsible were never charged.

Once, at a support meeting with Elders, the Chief Commissioner admitted that “The hard part about hearing all of this testimony is that I can’t stop thinking about it.” Later, he acknowledged, “I believed then, and I still believe today, that if I ever start crying about what I’ve heard, then I’m going to have trouble stopping.” (page 210)

Despite his upbringing, the TRC’s Chief Commissioner could not hide his disappointment in the response of our faith community, saying, “…as it’s turned out, senior representatives of the Catholic church comprise one of the strongest groups of deniers in Canada.” (page 209) Sinclair became a Fourth-Degree member of the Midewiwin Lodge, an ancient Ojibway tradition. His spirit name was Mazina Giizhik, “one who speaks of pictures in the sky,” which could be interpreted as a person gifted to philosophize, teach and explain. “I think that true reconciliation involves the ability to see that the teachings of Christianity and the teachings of Indigenous Elders going back thousands of years are compatible, and seeing how they are compatible.” (page 215)

The title of Murray Sinclair’s memoir asks the reader to ponder who we are in four questions: Where do I come from? Where am I going? Why am I here? And, Who am I?

The first question means we have to understand our relationship to the Creator and all creation. The other questions involve understanding “who your spirit is” referring to that spirit placed inside you by the Creator when you were conceived. The question is not just “what am I going to be when I grow up?” It also includes knowing what happens when I die. And answers to these latter questions can change throughout each life’s journey.

Murray Sinclair, Mazina Giizhik, has left Canadians with many good questions to ponder…and act upon.

Murray Sinclair, Who We Are: Four Questions for a Life and a Nation, McClelland and Stewart, 2024; 465 pages.

By Joe Gunn