Oblation and martyrdom

The Conference on “Oblation and martyrdom” that will be held in May in Pozuelo, Spain, invites us to reflect on a fundamental dimension of our Oblate vocation: martyrdom.

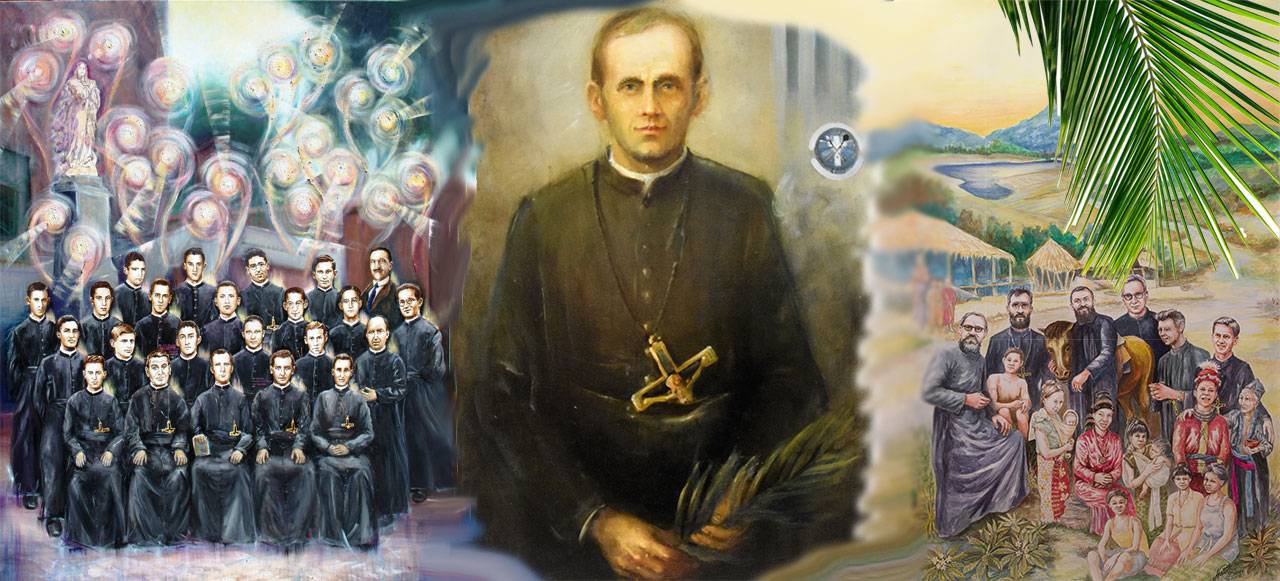

The first martyr among Oblates was Alexius Reynard, killed in 1875 in Canada by his guides during a trip to the mission of the Nativité. Ten years later, on April 2, 1885, Léon Fafard and Félix Marchand were killed at Frog Lake. Bishop Grandin used some meaningful expressions when writing to Father Fafard’s parents: “… Dear Madame Fafard, you may well compare your grief to that felt by the Blessed Virgin, and with even more reason than those who grieved the victim of Calvary: the dear martyr died for the salvation of his brothers and for the salvation of his killers.” To the parents of Brother Marchand he wrote: the two fathers “supported each other in their many difficulties, they were both victims of their dedication and martyrs of charity…” In 1913 two other Oblate priests dedicated their lives to their mission to the point of martyrdom: Jean-Baptiste Rouvière and Guillaume Le Roux, assassinated in 1913, in Coppermine.

We should also remember the martyrs of Spain, Germany, Bolivia, Chile, Sri Lanka, Philippines and Laos. Being an Oblate means to be ready for martyrdom. It is a recurring theme in the writings of the founder and the first generation of Oblates.

Here are just a few examples.

Towards the end of his novitiate, Vital Grandin wrote to his brother on December 15, 1852: “The name Oblate that I must carry brilliantly explains what I am committed to. I should be a victim, and not just a victim of a single moment, but every day. This is the true meaning of the crucifix that will be hung around my neck and it will remind me at all times that the Oblate’s path is a way of sacrifice and continuous immolation… To date there are no martyrs in our congregation. Oh! If I could only have the joy of becoming the first Oblate martyr!”.

During a retreat in 1888 from his place of mission in Saskatchewan, Ovide Charlebois wrote: “…All that I ask You (O God) is to accept every moment of my life as so many small acts of martyrdom. If I am not worthy to shed my blood for You, may my whole life become a continuous martyrdom. Yes, my God, from this moment I want to live like a martyr. Thus I offer You the martyrdom of my life, my good Jesus, and I sign this with my blood, so that You cannot deny me. I want not only my physical suffering to contribute to my martyrdom, but also and above all my moral suffering: temptations, dryness and distractions during prayer, my pride, etc… I want this to be my main act this day; I begin to live as a martyr. O Sacred Heart, teach me to live this way, since Your whole life was a continuous martyrdom”. That same year he noted, somewhat realistically: “Since my last retreat, a pious thought fills my mind…, that is to become a martyr; not a small claim, is it? You will, of course, now ask who will be my killers. It is very simple: the mosquitoes, my Pierric [an Indian orphan who, on the advice of Bishop Grandin, Father Ovide had welcomed to avoid living completely alone in the mission.], my school kids, my mistakes, my temptations, my anxieties, the hardships I must face, etc…, etc. It’s no small martyrdom of a few hours I want, but a martyrdom lasting a lifetime. Since not a single moment goes by without having to suffer, I have said to myself: why not accept everything in the light of martyrdom? Will this not be as acceptable to God as the momentary suffering of the true martyrs? Hence I feel as though above a brazier, that slowly burns me, thus keeping me alive for as long as possible”.

In 1866, Alexandre Taché recalled his 1845 arrival at the mission of Rivière Rouge. Thinking on the first missionaries there who had been massacred by the Sioux Indians in 1736, he wrote, “…let us pray then to this zealous apostle, that he might inspire in us the zeal to consume our lives in the service of this holy cause and, if necessary, to shed our blood for it too.”

This desire for martyrdom became a reality for many Oblates.

The idea of martyrdom had been most present in Blessed Mario Borzaga since his early years of training. This recurs constantly in his diaries: February 19, 1957 – “During the Via Crucis, with my crucifix in my hands, I fervently considered how Jesus has chosen me to continue His Via Crucis: a bearer of the Cross, a priest… Christ’s whole life was the cross and martyrdom. I am another Christ, so… I too have been chosen for martyrdom. And if I want to be a holy priest I should not wish for more, because this is the mystery that lies in my hands, every day: the mystery of the blood, of total immolation, of the complete giving of oneself, of the innocence due to renouncement, of humility before the divine grandeur”. April 19, 1957 – “Good Friday. The martyrs should be imitated, not praised!” June 26, 1957. “Today was the feast of the martyrs John and Paul… It is the martyrs who make the Church, only the martyrs …”.

The idea of martyrdom had been most present in Blessed Mario Borzaga since his early years of training. This recurs constantly in his diaries: February 19, 1957 – “During the Via Crucis, with my crucifix in my hands, I fervently considered how Jesus has chosen me to continue His Via Crucis: a bearer of the Cross, a priest… Christ’s whole life was the cross and martyrdom. I am another Christ, so… I too have been chosen for martyrdom. And if I want to be a holy priest I should not wish for more, because this is the mystery that lies in my hands, every day: the mystery of the blood, of total immolation, of the complete giving of oneself, of the innocence due to renouncement, of humility before the divine grandeur”. April 19, 1957 – “Good Friday. The martyrs should be imitated, not praised!” June 26, 1957. “Today was the feast of the martyrs John and Paul… It is the martyrs who make the Church, only the martyrs …”.

Maurice Lefebvre was killed in 1971 in La Paz, Bolivia. In fact, in December, 1967, Father Maurice had written “we too may see and accept what it will cost us to be disciples of Christ in 1968… It will cost us more than just mere words; it will cost us more than wishful thinking; it will cost us more than the translation of certain texts of the Popes and Reformers.”

Maurice Lefebvre was killed in 1971 in La Paz, Bolivia. In fact, in December, 1967, Father Maurice had written “we too may see and accept what it will cost us to be disciples of Christ in 1968… It will cost us more than just mere words; it will cost us more than wishful thinking; it will cost us more than the translation of certain texts of the Popes and Reformers.”

Michael Paul Rodrigo was assassinated on November 10, 1987, in Sri Lanka. On September 28, 1987, he wrote to his sister Hilda “… The Cross is not something that we hang on the wall or around our necks. Jesus was the first to be hung there… So we must be ready to die for our people if and when the time comes.”

Almost 100 Oblates died tragically during the exercise of their ministry. About thirty of them were proclaimed blessed and recognized as martyrs of the faith. A very small number considering the 15,000 Oblates who succeeded each other over 200 years, yet they are a sign of the radicality required of everyone from the oblation of ourselves to God, to the Church, to the poor.

By Fabio Ciardi, OMI

Published on the OMI World website.