A Priest, Prostitutes, Shelter and Care

Since 2005, Father Hermann has admitted more than 4,700 women with 10,000 children into his shelter program in Namibia – but due to his age and health issues, the future of everyone there is uncertain.

Photographs and text by Christian Bobst. Published on www.lensculture.com.

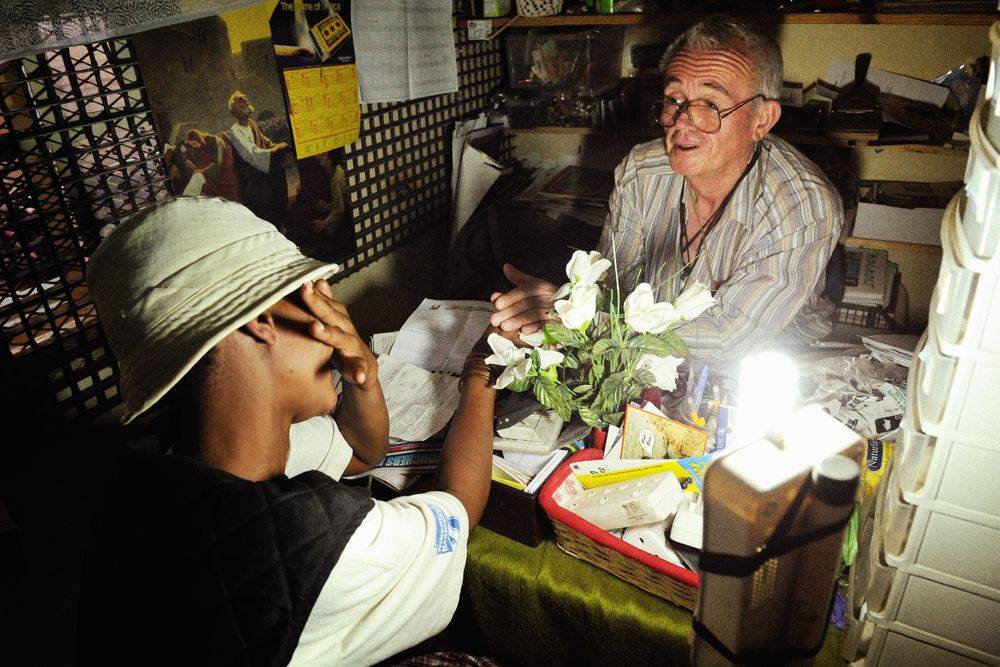

Father Hermann Klein-Hitpass has stood up for the weakest members of society in Namibia’s capital, Windhoek, for many decades. For the past 20 years his special focus has been caring for girls and women whose poverty has forced them into doing sex work. Most of those women do not call him “Father” only because he is a priest – many say that he is like a real father to them, the father they never had.

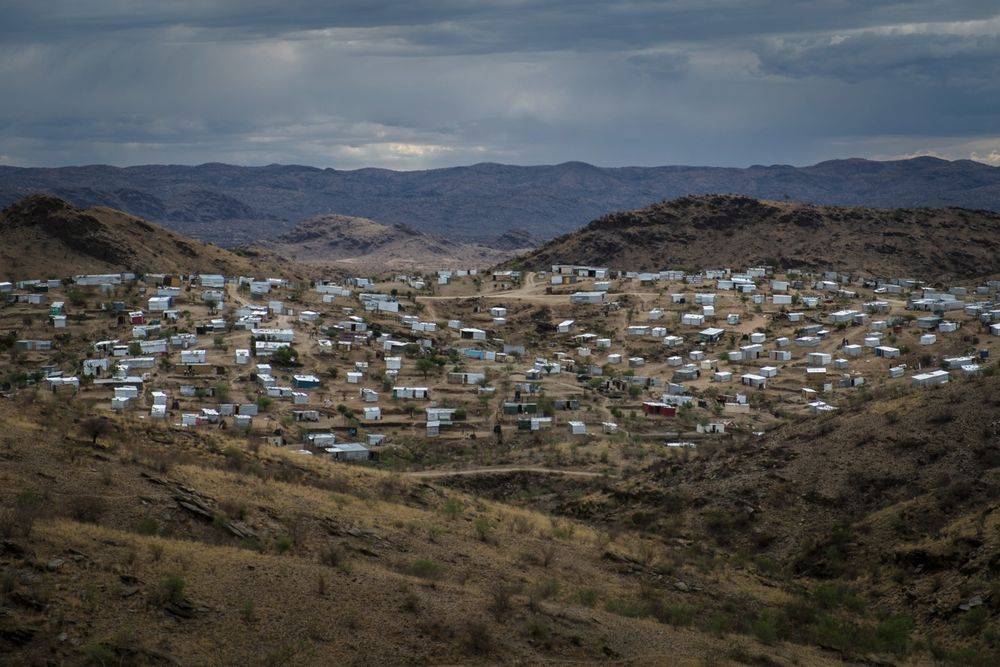

View on squatter settlement in Katutura, the largest township outside Windhoek. Katutura was created in 1961, following the forced removal of Windhoek’s black population from the Old Location, which is within the city. For single women, life in Katutura is very difficult, particularly for those with small children. Because there are few jobs, prostitution is often the only route to survival.

Whenever possible, Hermann ventures out into the townships to assist with problems or to get a sense of the conditions in which those he cares for are living. The priest talks to women and children on the street about the dangers of AIDS and other STDs. He encourages them to get tested for AIDS and passes out condoms – event though the Catholic Church forbids this. For Hermann, charity is always more important than rules.

Cecilia, 23, is one of the girls for whom Father Hermann cares. She and her two sisters were sold by their mother at the ages of 9, 10, and 11 years. At the age of 13, Cecilia’s younger sister Irène became pregnant and ran away. Irène tried to abort the baby with illegal pills, lost consciousness, was raped by a young man, and died. Cecilia and her sister Maria filed a lawsuit and brought their mother to jail, but they still have to sell themselves in order to take care of their children.

Hanna, 37, tells her story at her home in Damara 6, one of the roughest areas in Katutura. She says that she never knew her mother of her father, never went to school and grew up on the streets. She became a sex worker at the age of 16. Hanna expresses her gratitude for Father Hermann’s support. She shows her passport and explains that a few years ago some Chinese men promised her a better life abroad and paid for this document. Father Hermann convinced her not to go and kept her from making the biggest mistake of her life, she says.

Alexia, 28, became pregnant by her father at the age of 13. At that time, her mother was in the hospital; she died one day after Alexia told her that she was expecting a baby from her father. Her relatives blamed Alexia for killing her mother and chased her away from home. She survived by doing sex work for more than 10 years. With Father Hermann’s help, Alexia now runs a little shop and stays in a small house where she takes care of four other women and eighteen children.

Father Hermann talks to some women who bake bread dough in hot oil to sell at a nearby school. Years ago they were also working as sex workers, but they say they are now too old to get enough clients to survive. Namibia currently has an unemployment rate of over 40 percent, and the prospects of getting a job outside of prostitution are slim for most sex workers.

Young men hang around on a Sunday morning at Damara 6. By noon almost everyone is drunk. Women who live alone in the townships are at risk for being sexually assaulted by their neighbors or even by their relatives, especially when they are looked upon as prostitutes. Most of those abuses are conducted under the influence of alcohol or drugs.

Father Hermann buys some bread, butter and juice at a supermarket. In 2005, he opened a daycare facility for prostitutes and children where he distributes food and second hand clothes. The daycare was financed by the Catholic Church, partly because the church-goers were fed up with seeing the prostitutes who sought Father Hermann’s help at his quarter at the church.

A couple of girls from the Damara 6 area in Katutura help do each other’s hair. Sex workers in Katutura cannot count on the solidarity of their neighbors or relatives; they usually only get help from other girls who do the same work in order to survive.

At his daycare facility, Father Hermann distributes milk powder to prevent small children from contracting HIV by their mothers from breastfeeding. Once per week, sex workers who register with Hermann receive a ration of food and second-hand clothing. The amount is inadequate for survival, because the priest’s goals are not only to restore the women’s strength; he also wants them to learn how to perform regular work to become self-sufficient.

Children of sex workers are especially vulnerable. Most of them grow up in grinding poverty. When their mothers are dying from AIDS, they often have no other choice than to sell themselves in order to care for themselves and their siblings.

The stories Father Hermann hears are often nearly unbearable. Abuse, rape, physical mistreatment, AIDS and STDs are recurrent themes in the life stories of most of the women. Some commit crimes themselves: a few kill their children in despair, while others want to avenge themselves on men who have abused them by knowingly infecting them with HIV.

Eunice, 22, was one of a group of young children who were misused by an expat from Europe. As a consequence, most of the girls in the group later became sex workers. At the age of 17, Eunice was thinking about committing suicide.

Hermann tries to comfort a woman who suffers from severe depression after losing a baby. Many sex workers suffer from depression and suicidal thoughts, especially when they are infected with AIDS or STDs. Sick, weak and ostracized as whores, they have no chance of finding normal work and become trapped in a vicious circle.

Several women are fighting for a cigarette. Fights among the women at the shelter are not unusual and envy is a big problem. Therefore Father Hermann has to be very careful to distribute food and clothes at his shelter equitably.

Hermann starts work at five in the morning and often works until late in the evening, sometimes in areas where it is dangerous for white people to be out on foot after sundown. However, not all sex workers want his help, despite it being non-missionary in nature.

Many sex workers say that their children are their only joy in life. Because most of the men refuse to use condoms, these women often get pregnant. Some of the women have up to 10 children, often all from different fathers.

Father Hermann says his work is his personal offering to humanity, his way of doing what he can to assist the poorest of the poor and especially vulnerable children. But he is weakened by age and diabetes, and is reaching his limits. Hermann says that he will have to give up the daycare soon because there is no successor and his strength is fading.

More and more men are seeking very young children for sex, because they think that children do not have AIDS or that HIV infections can be cured by sleeping with a virgin. Father Hermann says some of the most disappointing and hurtful cases are those in which parents force their children into sex work as a means of survival – or just to buy alcohol.

Since 2005, Father Hermann has cared for 4,700 women with 10,000 children at his daycare facility. For almost 20 years he reported the stories of those women and raised money by writing letters to private donors. In 2012, he was awarded with the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.