Simply Juan

“In these eight days that follow I imagined that Juan is in his spiritual exercises, as was in his plan”. So Thelma consoled herself as she walked thoughtfully with her daughters Claudia and Julia behind her husband’s coffin in the parsimonious funeral march in the hot sun of Tocoa, Colón on the afternoon of Monday 16 September, accompanied by shouts and slogans of indignation from the hundreds of people who gathered to say not just a goodbye to Juan López but a yes to continuing the struggle he led together with many people committed to the defence of the environment, land and human rights.”

In Fabio Ochoa

His murder, millimetrically planned, occurred after eight o’clock in the evening on September 14 2024 when Juan had left the chapel of his neighborhood Fabio Ochoa, a community of settlers that came from a land seizure in the middle of the last decade of the last century, promoted by peasants and settlers without a plot of land, all of them animated by faith and their link to the Catholic Church. The name is due to Don Fabio Ochoa, then a union leader of SITRAINA, who led this struggle in 1997 while he was running for deputy for the then nascent Democratic Unification Party, a party organization founded by left-wing exiles who returned under the amnesty decreed at the beginning of the 1990s during the government of Rafael Leonardo Callejas.

Carlos Escaleras, a defender of the environment, also belonged to this party organization. He had been a candidate for mayor in the municipality of Tocoa when he was murdered in October 1997, a month before the elections. So too Juan López had officially declared his candidacy for mayor on behalf of a current of the LIBRE party. Don Fabio Ochoa also led the demand of hundreds of ex-banana workers of the Standard Fruit Co., victims of nemagon fungicide, with which the banana plants were sprayed, resulting in sterilization, cancer and other fatal damage to the lives of the workers. As a result of this struggle and the trade union and agrarian struggle, Fabio Ochoa was the victim of an attack from which he emerged alive, but with physical disabilities that deprived him of normal mobility. In this area of Aguán Valley, it is not easy to find someone in popular leadership who dares question the traditional powers with local, national and international ramifications, and who is still alive to tell the tale, or with the physical capacity to continue in the struggle.

Juan’s family, along with dozens of other families from the parish, were beneficiaries of this recovery of urban land, and since the end of the previous century they have lived and organized their lives around neighbourhood solidarity and the experience of the basic ecclesial communities. With Juan’s enlightenment and persistence, most of the families decided to settle in the colony without relinquishing their small property, which they had won through a tenacious community struggle.

At the last minute

Juan got into his car, along with his wife Thelma and his daughters Claudia and Julia. Then his neighbouring comadre got in, but he did not start the car because her husband was closing the door of the chapel. The comadre wanted to leave soon because they were going home and she had to prepare the dough to make the flour tortillas for the baleadas. That night Juan and his family would have baleadas for dinner with their compadres, as they often did. As well they had to go to bed early, not only because Juan was tired after more than a week of travelling around the Sula Valley and areas of the western part of the country, accompanying his bishop Jenri Ruiz, but also because the next day, Sunday September 15, he had to accompany his nine-year-old daughter Julia, full of innocent excitement, to the traditional parade in her brand new dress and shoes. It was the fifteenth of September, Juan could not help but bask in the sunshine watching the youngest of his two daughters in the parade.

Julita tells how she saw a man with a motorbike helmet standing nearby without entering the chapel. After Juan finished preaching, her father approached her: “My love, whatever happens, I will always love you,” he told her. And Juan returned to the altar for the closing prayers of the Celebration of the Word. Julita usually reciprocated with a kiss and the heartfelt “I love you”. At that moment she didn’t respond, she frowned, like when she complained to her daddy why he took so many days without coming home. This time she didn’t speak, she cut herself off, her gaze followed her father’s footsteps as he returned to the altar. And that was Julita, when she didn’t understand things she kept quiet.

A few years ago – in 2019 – Julita heard her father discuss with Thelma, her mother, whether or not to turn himself in to the police. Her mother asked him, she begged him not to do it, she did not believe in prosecutors or judges. “You’re going to stay in prison, Moreno,” she said, “and then no one will be able to get you out.” Julita listened, she said nothing. Juan decided to turn himself in, and his decision led the other land defenders to also turn themselves in. The decision of the courts was, as Thelma said, to leave them locked up for who knows how many years. However the power of such immense popular support in solidarity was that they could not remain locked up indefinitely. And on that occasion, solidarity triumphed. In her innocence, the little girl told her daddy with simplicity, “if I had asked you not to go to prison, would you have obeyed me“. But she didn’t, as on this occasion of foreboding immediately shortly before his death. Maybe she could have said, “daddy, if you told me you would always love me, then I ask you not to leave here, there is an ugly man outside”. As when Juan decided to give himself up to the filthy justice system, Julita kept quiet.

Juan hesitated to start the car, waiting until his compadre got in after leaving the door of the small Catholic church locked. When the compadre got in, Thelma saw a man with a helmet and a black mask coming towards them. Juan saw him too, and before he knocked on the door on Thelma’s side, he asked who the guy was. And as if he didn’t suspect that these were the last moments of his life, he pressed the button on the left side of his door which automatically opened the glass of the window where the man Julita had seen a few minutes before was standing. Then Thelma saw the man’s gun, and shouted “Juan, close the window!”, at the same moment that she grabbed the murderer’s gun, she struggled for eternal moments until she hit her hand. The first shot deflected off Juan’s body and went through the glass in front of the car.

The assassin then positioned himself diagonally to Juan, warned the rest of the passengers, directing three movements with the hand that wielded the gun at Juan, thus indicating that he was not coming to kill anyone else, that the order was clear: kill Juan, taking care not to kill anyone else. And the shots began to cross the glass and hit the body and face of the man who had never used a firearm. There were seven shots. Accurate. None of them missed. Only the shot that was deflected by Thelma, Juan’s beloved and confident wife, missed.

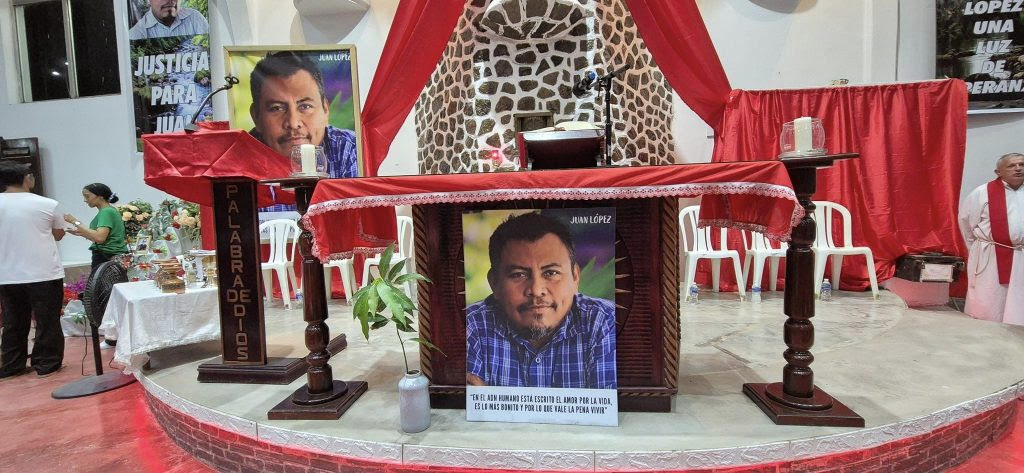

During the wake of Juan López. Photo Radio Progreso.

“They have just killed Juan!”

That Saturday I had had a rather quiet afternoon, with mass in the evening accompanying the first communion of a godchild and then attending the birthday that her daughter and granddaughter had prepared for Mami Lencha with all their pomp. With her weakened body she was grateful to be celebrated on her 90th birthday. During these religious and festive activities I was accompanied by a couple who were close friends of Juan’s. We returned home after eight o’clock at night, and before going in I asked them to please not make any noise because I was not going to wake up until seven in the morning. I had had a busy week and I wanted to rest. I parked and turned off the car’s engine.

The three of us got out, and I hadn’t finished putting my rucksack down when my companion approached me with his right hand trembling, “speak, speak“, in a faltering and hesitant voice, he said without looking at me, rather looking down. I was surprised by the intense trembling of his arm and he handed me the mobile phone. I took the device and heard the disconsolate voice of my colleague Lesly Banegas, “Juan has just been murdered“. Those words punched me in the gut like the early morning of March 3 2016 when Gustavo -Tavito-Cardoza called me to tell me that Berta Cáceres had been killed. And like when on November 17 1989 I was told that my Jesuit brothers at the UCA in San Salvador had been murdered. Or when on December 9 1991 they let me go without anaesthesia that Chungo Guerra, with whom two days earlier we had planned national activities to demand that the neoliberal adjustments not be applied, had been assassinated with a shot to the head. Or on October 17 1997, when they called me at night to tell me that Carlos Escaleras had been murdered.

There are blows in life, as the poet would say, and I always think that this will be the last one, and suddenly new blows come. And even if there have been many blows, and even if they have called you ten times, twenty times, sixty times to give you the blow of the death of a friend, each blow feels as if it were the first. Or perhaps more clearly, in each blow all the previous blows are concentrated in one huge punch.

Same pattern as with Berta

Juan was murdered. The news was all too clear when my journalist colleague Lesly Banegas gave it to me, a few minutes after the fact. He was murdered with the final explosion of a prolonged process. It was not a one-time murder. When at eight o’clock on the night of September 14 2024 the hitman pulled the trigger to pierce Juan’s body, a murder that had been precisely constructed was finished. The similarity with Berta is striking.

First and for a long time, the people in power ignored Juan. Even with his short stature and indigenous bearing Juan was one of those people who, to the stereotypical world of tall, white, straight-haired, non-Indian, university-educated people, which is typical of a racist society like the Honduras, went unnoticed. The media, what they call the media matrix, ignored him. Juan did not exist for the big movers of national influence.

This assassination drew the attention of eyes and ears everywhere. Then they realized not only that he existed, but that he had wide recognition in the communities and in the grassroots Church, even being recognized as an assistant to bishops, so much so that in the Sunday Angelus message of September 22 Pope Francis dedicated almost a minute to him. For the society that defines racism in Honduras, Juan was born with his murder and finally recognized by the national media. With all that Juan did working like a humble ant or as a spider weaving popular dreams, no national media interviewed him because of the power he had.

Second, Juan’s word made the powers in the Aguán area, particularly in the municipality of Tocoa, uncomfortable, which is why they tried to neutralize him; dozens of times they tried to co-opt, bribe or buy him. From the offer of money to shady negotiations between politicians they sought to turn Juan. He turned out to be even more uncomfortable because no amount was sufficient, he could not be bribed or bought.

Thirdly, as he could not remain anonymous and could not be neutralised with bribes, he was stigmatized with all sorts of fabrication, even accused of being a murderer, of being responsible for the instability in the area, of promoting revolts and violent activities. Juan the violent agitator, that’s how he was stigmatized. The very one who was never heard to use an insult, let alone known to carry a weapon. Stigmatization creates adjectives, atmospheres, and generalizes a narrative so that people who saw Juan passing by or seeing him at a meeting immediately thought he was planning violent acts.

Fourth, Juan was also criminalized. He was accused of arson, of being a member of illegal or terrorist organizations and even accused of murder. He was imprisoned, and had to seek refuge to escape the arrest warrant that was issued against him, and because of the death threats he constantly received over at least the last six years.

Fifth, and finally they took his life, as the culmination of a process of treachery, premeditation and advantage. They killed him because they could no longer tolerate him. They wanted to get him out of the way; prison was no longer enough; threats and stigmatization were no longer enough. They had to kill him, they had with such treachery to kill him. And they coldly premeditated the crime. They designed it meticulously, even finding the appropriate night. They knew that Juan could miss any meeting or ceremony, but what he would never miss was the Celebration of the Word of God in his community of Fabio Ochoa. This they knew all too well. This symbolic place of non-violence, the Catholic chapel, was chosen by those who planned the crime to execute him, that is, the non-violent place became the scene of violence, and the violent ones assassinated Juan “the non-violent” in the place where Juan preached peace, justice and solidarity.

The massive convocation for the wake

The wake and the funeral were charged with mixed feelings and thoughts. The 48 hours of ceremonies were not enough to bring the crowd out of their shock and rage. There were no people who knew Juan – and there were hundreds of them – who did not weep bitterly, exactly as one weeps for a very close relative, as indeed Juan was for all the people who gathered. First people gathered at the cultural centre of the parish of San Isidro, and then at the funeral home with air conditioning, for it was decided necessary to preserve the body from the burning heat that always, but more so in this season, seems that at any moment the living flames will come out of the earth, and even more so with the cement that is increasingly abundant in the urban centres.

All the people cried. Sometimes the jokes and anecdotes came out with awkward humour, but returning to the reason why the community felt called together, the sadness turned to tears. It was the largest community and popular gathering I have ever seen since the wake and funeral of Berta Cáceres. It was an occasion for compadres to meet, for godchildren to meet their godfathers and godmothers who after baptism had never met again, for the divorced to meet again after their separation, and to greet each other or at least exchange glances, for many to greet or meet the priests of Tocoa and of the diocese. I was reunited with hundreds of people I had not seen for at least three decades.

“You married us 34 years ago,” said a lady with obvious wrinkles covering her face. Another voice immediately followed, “and you married me 30 years ago”. “You baptised my children 32 years ago, but notice that they married evangelical women, and they did not return to the Catholic Church.” It was an occasion for nostalgia, to talk about youth and past gatherings but now with joints and legs limp from arthritis. As a consolation facing the sting of such crime, they extolled past triumphs and struggles that perhaps were not so great, and they spoke of future struggles without any present foothold. Yesterday’s trade unionists turned into today’s small businessmen, land defenders turned into business people or more than a few into coyotes, experts in transporting migrants, they came together. There was everything in the 48 hours of pain and candlelight. There was no aguardiente or cards, but there was plenty of coffee and chicken and beef soup.

Funeral Mass for Juan López at the San Isidro Labrado Parish Church in Tocoa, Colón. Photo Radio Progresso.

A foreseeable and avoidable murder

Juan’s murder was foreseeable. During the last five years he tried to avoid it with various measures, some of which he accepted voluntarily, others he had to accept bowing to pressure from his friends, but against his will. With his family and other families, he moved from the area, first to avoid imminent imprisonment in view of the arrest warrant issued by the court, but above all to protect himself from the insistent and insidious death threats that he and his companions received through their mobile phones as well as from unknown callers. Smear campaigns continued by some of the media communicators in the area, who over the last five years at least, had been denouncing the activity of the environmentalists, and particularly of Juan López.

After his assassination, many people say that this end could have been avoided. And it is true, not only was the state negligent, especially with its justice institutions, clumsily allied with the mining companies, the military and local and national politicians. As well the Public Prosecutor’s Office, SERNA and the Government of the Honduran state have also biased their decisions in favour of those who have exercised the law of the strong to impose their investments at any cost, contrary to the good of the environment, the communities and Honduran laws. In addition to negligence and deliberate delays, there has been the collusion of high authorities to tilt the decisions of the State in favour of the powerful businessmen, especially Mr. Lenir Pérez and his wife Ana Facussé, and other local politicians led by the mayor of Tocoa, Adán Fúnez.

Touching the fundamental nerves of a company

It could have been prevented, perhaps it was delayed, but Juan and his people touched the raw nerves of the speculators and the interests of the real owners of the economy and of the country’s fundamental decisions. In the Montaña Botaderos National Park, Carlos Escaleras, a legally protected area, mining investments were set in motion with the full backing and collusion of the state through Inversiones Los Pinares. At the same time, Inversiones Ecotek constructed in the Park a factory to process the iron oxide extracted from the mine, accompanied with the installation of a powerful thermoelectric plant to cover the energy demands of both the mining and the processing factory. There were links with the airport industry, primarily Palmerola, but with an impact on the country’s other airports, and a power plant based in Planes, also in the Aguán. Connected to all of this is the powerful metal roofing and construction industry under the name of Alutech.

An emporium was set up and consolidated over barely two decades, and in which it is an open secret that Juan Orlando Hernández and several of his trusted circle, as well as politicians and several prominent names in the political leadership, have put their hand in as partners. In its advertisements , the EMCO group promotes its mining exploitation with the argument that it complies with all the standards of respect for human rights, care for the environment and developing sustainable energy. However, in only three years, the central area of the national park Botaderos Mountain, where the rivers Guapinol, San Pedro, Cuaca and Tocoa originate, has become a barren wasteland, without trees, leaving the river basins practically dry.

The installation of the mining industry has brought violence and displacement, bitter division among neighbours, the displacement of dozens of families, the imprisonment of members of the Municipal Committee and the previous murder of three members active in the defence of the environment. In this small piece of territory, the country’s largest de facto groups have operated in association with foreign investors. In the underground corridors of these investments, the innocuous traces of drug trafficking have been present moving with invisible tentacles, but expressing itself through visible and legal powers, without which it could not exist or achieve the power it has acquired in Honduras. Juan López and his people confronted these powers.

View of the central zone of the Carlos Escaleras National Park, affected by the irregular exploitation of the mining company Inversiones Los Pinares. Radio Progreso.

Justice officials, servants of the emporium

For at least eight years – 2016-2024 – the visible drivers of these powers sought to ignore Juan and his companions, and then tried to bribe and neutralize them. When they failed to do so, they set the media machinery in motion to stigmatize them as violent, as enemies of development, or social misfits, in short, everything they did with Berta Cáceres. And they went on to criminalize them with lawsuits. The justice system – through the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the judiciary – acted diligently in favour of the powers that be. They launched themselves like wild beasts against Juan López and his community. From October 2018 to February 2019, Juan and the members of the Committee received death threats, and the Public Prosecutor’s Office issued legal summons against Juan López, Reynaldo Domínguez and Leonel George and 28 other people from the communities of Guapinol and Sector San Pedro. This was followed with arrest warrants and the accused had to seek refuge in order to evade capture. In February 2019, after extensive consultations, discernment and deliberations, they took a decision that established a turning point in the lives of those directly involved and in the life of the Committee. They decided to turn themselves in to the competent authority, knowing that such a step could leave them rotting in prison.

For many, this step meant not only imprisonment but also burial. They were taken to the Támara prison, near the capital, which sparked the mobilization of social organizations. The mobilization was powerful, when in those times taking to the streets and putting pressure on state institutions was immediately followed with tear gas and the character assassination strategy of the media matrix. In those periods social, popular and human rights organizations were not as co-opted and neutralized by the government as they would be a few years later. The community struggle was linked in an extraordinary way with international solidarity.

“Guapinol, Guapinol, we are with you”

The name Guapinol achieved universal recognition. Before 2018, if you spoke of Honduras to an international group, and if foreigners managed to locate the territory on a world map, they would think of the ruins of Copán or the islands of Roatán, or perhaps they wondered about the capital with the strange name Tegucigalpa. After the national and international demonstrations demanding the release of political prisoners, people began to think differently of Honduras and immediately associated it with Guapinol, with its enthusiastic slogan “Guapinol, Guapinol, we are with you”. This is what I heard Julita, the youngest daughter, shout when Juan and his family were imprisoned.

National and international pressure, plus the expertise of the team of lawyers, succeeded in freeing Juan López and companions from jail after two weeks in prison. But eight other comrades in the same struggle in defence of the Guapinol River and in full opposition to the extractive activities of the Pinares company, were captured and locked up in La Tolva, one of the prisons for highly dangerous prisoners. After pressure and legal action by the legal team, the eight environmentalists were transferred to the Olanchito prison, in the department of Yoro. They were incarcerated from 31 August 2019 until 24 February 2022. And they would have remained imprisoned indefinitely – since that was the decision of the owners of the company Pinares and Ecotek, from where the orders to prosecutors and judges in the area came from, orders normally mediated by “that sensation of tenderness that money produces“, as the Yoro poet Roberto Sosa once wrote. So it would be if it had not been for the pressure led by the Municipal Committee in Defence of the Common and Public Goods of Tocoa, national solidarity and international solidarity, together with a team of solidarity lawyers with extraordinary capacities both in the professional field and in their ethical and social commitment to the communities that are victims of the extractive company Los Pinares and Ecotek.

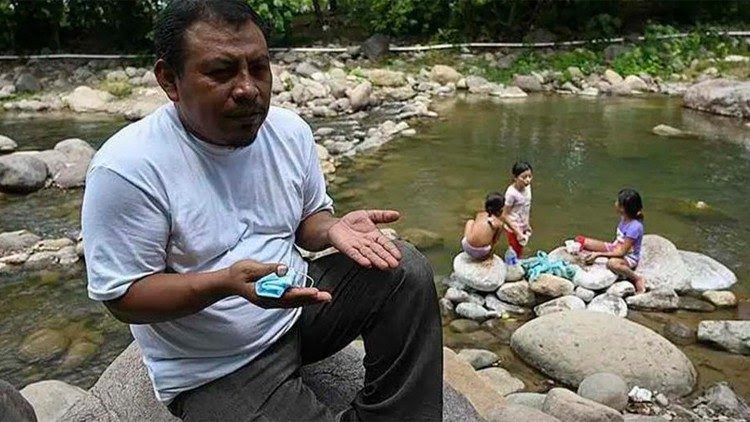

Juan López, criminalised in 2019 for defending the San Pedro and Guapinol rivers. Assassinated five years later, on 14 September 2024.

To ride out the storm without running away

The death line had been drawn. As with Berta Cáceres, the pattern of extermination of environmentalists had been followed to the letter with Juan López. As has been said, from ignoring him, seeking to bribe him, stigmatizing and criminalizing him, to assassinating him, Juan Lopez was able to weather the situation on several occasions. His greatest effort in his last five years was to resist the death machine. And he did so with impeccable tenacity while defending his community’s water, the environmental rights of his people in Aguán, celebrating the faith from his unwavering commitment to the defence of the common home and meeting with various organizations throughout almost the entire national territory.

They joked that Juan was like the Holy Spirit, he could be found wherever there were meetings and activities in defence of the common home, human rights and the defence of the earth. The acutest of the jokes said that if you wanted to see Juan López you had to look for a place where there was a meeting, wait an hour, and you were sure to see him. Defending the environment and protecting his people in the face of threats, even from those who were embedded in the municipal structures of his municipality of Tocoa, was his primary refuge to protect himself from the death that surrounded him. It was written in stone with such a despicable, vulgar and infamous expression that was directed at him on multiple occasions: “andás cargando las tablas” (you walk carrying the stone tablets).

Three branches, one common trunk

Local, national and international fingers all point to three clear branches from where the payment of the triggermen must have come. These three branches have a common trunk in what we generically call organized crime, or the extractive emporium with its very diverse ramifications.

First branch

The first branch has the finger pointed at the mayor of Tocoa, Adán Fúnez, with whom Juan López had altercations, confrontations and permanent disagreements. Three days before his assassination, Juan López demanded the mayor’s resignation at a press conference, and that if he did not do so, the Juan suggested that the people should remove him. A few weeks earlier, a fire broke out in the building of the municipal mayor’s office in Tocoa, in the heat of the confrontations between the mayor and the municipal committee led by Juan López. Prior to this event, the Committee had held a municipal assembly to demand that the state implement Decree 18-2024, which declared illegal all mining activities in the Botadero Carlos Escaleras National Park, as well as declaring all parts of the reserves in Honduras free of any type of commercial exploitation.

The Secretary of Natural Resources, SERNA, dragged its feet in fulfilling its function, just as the head of that secretariat withheld the text of the Decree for nearly two months before it was published in La Gaceta. The die was cast against the owner of Inversiones Los Pinares and Ecotek, Lenir Pérez. Legally, all was lost for him. He also failed to get the mayor to approve the installation of the thermoelectric plant that would be used for the operation of the mining industry, under the argument that it would also supply electricity to several communities surrounding the installations of the industrial emporium Inversiones Los Pinares. At the same time, in June 2024, the Tribunal of Honour of the Libertad y Refundación Party (LIBRE) summoned the mayor of Tocoa, also a member of that party as was Juan López, regarding his actions in a public document in which it demanded that he answer several questions about his possible support for Inversiones Los Pinares and not having accepted the popular will expressed in the Open Town Council held in Tocoa on 9 December 2023, in which a massive vote was registered against the installation of the thermoelectric plant. There were many other troubling questions about the dubious political performance of the mayor as a member of LIBRE.

Mayor Adán Fúnez did not respond to this summons. In the days following the fire at the municipal building, a video dated 2013 was released in which the mayor of Tocoa appears as an intermediary between recognised drug-trafficking leaders to accept money for the political campaign of LIBRE, whose candidate was Xiomara Castro Sarmiento, with former president Manuel Zelaya as the real architect and developer of the campaign. The legal fate against the mayor of Tocoa was sealed. To take revenge on Juan López, who had ruined his life, uncovered his misdeeds as a thug, as a protector of criminals and as partner of the mining businessmen, would surely have been contemplated by someone who had considered himself a proprietary member of the municipality. A front man for crime and a cover for a multitude of illicit acts, Fúnez deserves to have the accusing finger pointed at him as a candidate who could have paid the gunmen to eliminate Juan López.

Second branch

The accusatory finger points to a second branch – that of Lenir Pérez and his closest and most public partners in Inversiones Los Pinares and Ecotek. It is from this source that most of the threats, stigmatization, media smear campaigns, and accusations against Juan López and his associates have come. It is from this business nucleus that decisions have emanated from the Public Prosecutor’s Office in the form public prosecutor’s summons and from the Judiciary came arrest warrants, imprisonment, convictions and sentences for the environmentalists led by Juan López. This murder was a consequence of Juan López’s tireless mission in defence of the Guapinol, San Pedro and Tocoa rivers, of his national and international denunciation of Inversiones Los Pinares and Ecotek. Juan López led the struggle to successfully stop the installation of the polluting thermoelectric plant, and having succeeded with environmental pressure that culminated in the approval of Decree 18-2024 which prohibits all exploitation along the Montaña de Botaderos, Carlos Escalera national park, as well as the sanctions and demands against those who caused damage to the area. Lenir Pérez and his close associates are surely suspects in the murder of Juan López.

Third branch

The third branch of accusation points directly to the military and its obvious links with organized crime, especially drug trafficking. From highly credible sources it is known that the genesis of the mining exploitation was very close to initiatives associated with the criminal Cachiros group, so much so that Adán Fúnez himself, in an assembly with the communities of Guapinol and the San Pedro sector, recognized that those investments came from the generosity of Javier Rivera Maradiaga. Suddenly, and as if by magic, Lenir Pérez and Ana Facussé appeared as the investor owners of Inversiones Los Pinares. It is public knowledge that the military, through well known officers, have deployed strong contingents of army personnel to provide protection for the investments, and with financing from Lenir Pérez a large number of members of the Armed Forces graduated to fulfil private security functions.

All happened with the approval of the high command of the Armed Forces and the government of Juan Orlando Hernández (currently jailed in the USA for drug and weapons smuggling), who is said not only to have been aware of the army’s role in the security and intelligence services of Inversiones Los Pinares and Ecotek, but also to have become an investment partner of the company. In this way, political leaders, private investors, high-ranking military officers and drug traffickers are said to be linked to this extractive corporation. It is this nucleus of power that would be at the root of the tradition of impunity that would lead to the murder of Juan López.

To build a multi-coloured story

It is commonly said that the story of the Aguán can be told in green, brown, white and red. Green because everything that has happened in the Aguán against the campesino communities and its inhabitants has been in the colour of the military uniform. The brown colour of the fertile land of the Aguán has been a factor in the violence led by the military, at least from the 1970s to the present day. It was well said in those fateful years of agrarian struggle that whoever controlled and owned the land had the power. This has always been the situation, although in the present century the power of land has been combined with territorial control led by the powers that move in the underground corridors of organized crime. Always with the military presence there has been bloodshed. In the mining and environmental conflict, the brown colour of the land has been a factor in its control by the EMCO conglomerate, not to cultivate and produce from the land but to seek the underground wealth that lays below the surface.

The military have always had the function to protect those who have controlled the land, and they themselves – the senior officers – have in turn become the core of new landowners. They have not only looked after the land, but also appropriated it. Way back in 1989, a group of peasants seized land on the left bank of the Aguán river, based on the right they had to work on agrarian reform land. The battalion colonel summoned them to a meeting, and warned them that if they did not vacate the land within five minutes, they would all be imprisoned. Overcome with fear, the peasants left the land. It soon became known that the colonel himself took ownership of the land.

Over time, the colour white gave the Aguán valley a new and gloomy identity. It became the main route for the passage of drugs from the Moskitia across the imposing Aguán valley, through the Lean valleys, across the mighty Sula valley and on to the Guatemalan border. The white was the colour of the drug protected from the beginning by the military, who opened the Honduran corridor so that the drugs from South America would have their strategic control point in Honduran territory on their way to the United States. The white cocaine powder has always been associated with the military’s olive green colour.

Meanwhile the Aguán Valley with its peasant and popular struggle has been stained red with the blood of defenders of the land, fighters from their popular and peasant organizations and later the defenders of the rivers and their threatened territories. The red green of the peasant and community blood has mixed with the brown of the land and the white of drugs, as a macabre expression of the olive green activity of the military that has safeguarded the interests of landowners, cattle ranchers, traders, politicians and drug traffickers.

State conspiracy and full collusion

The state was always present in the Aguán while Juan López and the members of the Municipal Committee were persecuted and criminalized. It was actively present favouring the company Inversiones Los Pinares and Ecotek and in direct collusion with Mayor Adán Fúnez. The administration of Juan Orlando Hernandez was in full collusion, as enabler and as a business partner. High ranking politicians and officials were always present, as is the case of the Ministry of the Interior, which did not lift a finger to proceed ex-officio in response to the denunciations of the behaviour of the mayor of Tocoa. De facto the military has always been present. The political state apparatus was activated against Juan López and his followers. The defenders of the Guapinol, San Pedro, Cuaca and Tocoa rivers were under direct attack, persecuted and criminalized by the public prosecutor’s office and the judiciary. Since the advent of the LIBRE administration the state has continued to be actively present, but trying unsuccessfully to remain under the radar. It was the same as during the time of Juan Orlando Hernández, but now with cautious discretion, that is to say, hypocritically.

LIBRE, like Pilate in the Aguán

Adán Fúnez was always ratified by LIBRE and its spokespersons always endorsed his actions. Not even when the Court of Honour rebuked him in June 2024 did the ruling party stop backing him. Not even when the narco-video appeared has there been a firm stance from the governing party’s leadership. It is certain that the National Congress did approve Decree 18-2024 to protect the Montaña Botaderos National Park, Carlos Escaleras, but SERNA did not act in accordance with the Decree’s demand to definitively cancel the industrial operations and to file lawsuits against the company to seek compensation for the damage caused to the eco-system of the area and the communities directly affected. Nor was a plan defined to progressively restore the destroyed core area of the national park. The state remains involved with the same intensity as before the current government, but with the greensplaining language of protecting the environment without giving protection to environmentalists.

A cowardly active presence in relation to environmentalists.

This leads to the conclusion that the state has a heavy share of the responsibility in the assassination of Juan López. The demands presented to the state for this crime should include support for the environmental organizations to preserve the memory of this distinguished defender of the common home. The LIBRE party abandoned him. After his death, it vindicated him, but the party’s leadership structures had other priorities – the mayor was the one who received protection. As expected, true to its nature the party washed its hands of him: but nothing removes the stain of betrayal for failing to protect a faithful militant, albeit one who was an irritant because of his constant questioning.

Juan, the child of La Coroza

I met Juan in 1990. I was a member of the pastoral team of the parish of San Isidro Labrador, in Tocoa, Colón, when the territorial extension of the parish covered the municipality of Tocoa, the municipality of Bonito Oriental and part of the municipality of Trujillo, on the left bank of the Aguán river. It was my turn to make pastoral visits to Bonito Oriental. I liked it when the schedule of visits included the Achiote, Mona and Coroza corridor, in the beautiful mountainous massif of La Esperanza. Those communities were only a few kilometres from the dividing line with the department of Olancho. I liked to go to La Coroza, a small community made up of peasant families mostly from Copán on the border with Guatemala. They were “Chortíes”, it was not clear whether they were from Guatemala or were born in Honduras. They valued their roots as a treasure.

They would only said they were from Copán Ruinas, but it was once heard that they could be from Jocotán or Camotán, already in Guatemalan territory, just where Castillo Armas’ troops organized themselves to advance towards the Guatemalan capital, where they would lead the coup d’état in 1954 against the progressive government presided over by Jacobo Arbenz, on orders from the United Fruit Company.

They were mostly short, reserved people, who said only what they needed to say, but communicated more with body language. I loved going to La Coroza because even in my early thirties, I loved to walk along a path skipping stones over 17 fords of that beautiful ravine that descended from the mountain, leaving its murmur that mingled mysteriously with the noisy silence of the almost virgin forest of cedars, laurels and mahogany trees. Jumping over the rocks was one of my greatest amusements in those early days of the mission. My aim was to come out of the 17 stone crossings undefeated. I rarely succeeded, and although my falls into the streams were thunderous, I never had a single fracture in those days of hard and sturdy bones as I was never to have them again for the rest of my years. I had a lot of fun because I was always accompanied by youngsters who stuck with me before the 17 crossings before reaching the village Las Palmas made up of some 60 families, all of them Chortís. There I managed to hear the testimony that all of them were born beyond the Honduran border, in the Guatemalan village of Camotán and its surroundings.

I used to call those indigenous families who seemed secretive, distrustful, and with a conservative mentality, Cimarronas (runaways). No wonder! They came from repressive environments in the mid-20th century, under the relentless rule of the Guatemalan army, subjected to fierce anti-communist propaganda. Unable to live their lives in a land that was both arid and dominated by landowners, they crossed the border to live for a time in the municipality of Copán Ruinas.

After a few years without work, they heard about the miracles of the agrarian reform in the Aguán valley and continued their exodus. Some families settled in the valley, forming the community of Las Palmas, while others made their way up the hill and settled on the banks of the beautiful La Coroza stream near its source, and decided to call their settlement “La Coroza”. One of its founders was the grandfather of Juan López. But Juan’s grandfather, with an unshakable faith, knew how to hear the breeze and know where the winds were blowing. This is how he listened to the Church and knew how to break through mistrust to open himself to the renewing winds of the Church of the poor. This is how Juan received it from his childhood. And he was one of the little boys who waited for me in the community of Las Palmas to take the road upstream against the current of the ravine. He would jump over the stones with me with a skill that I never managed to achieve.

The dirty tricks in Las Palmas

I liked to pass through Las Palmas, not because the families were so overtly religious. They were rather sullen, they attended mass and that was it. They avoided talking, especially the women. Organizing in councils, youth groups or women’s organizations did not inspire them with the slightest enthusiasm. When they heard about grassroots organizations or base communities, they closed themselves in their homes or in their work plots. The anti-communist propaganda that they or their parents received in the middle of the century still caused fear. But there was no lack of humour and fun among the young people, and that’s what I liked about the community, so I would pass by and stop there. As was obvious, there was no electricity, so the prayer house was made of adobe and was lit with lamps, candles and torches. But the light was indoor only and nothing could be seen outside. The women, as usual, would wear their best dresses to go to the religious celebration. The children would be playing around the house of prayer. Some were throwing compliments to the girls, others were more daring, inviting their sweethearts to sneak away.

The most mischievous of them had a literally dirty game. As the building was made of adobe, and as it was in the dark, they could see inside. They would look for a very long stick, and then poke it through the cracks in the prayer house wall to touch the girls’ dresses. It was a disgusting game because the boys would take the long stick that they cut, smear the tip with feces that they collected from the bush where people went to relieve themselves due to the lack of latrines and then rub it on the girls’ clothes. The council decided to move the benches away from the walls, but the kids only upped their game with longer sticks. Next the council covered the walls with plastic, but the kids broke through it easily. Next they set up security guards, but the inventive youths in those areas knew all about it, because even some of the guards got caught up in the foul play. Finally the council decided to move the celebrations to three o’clock in the afternoon.

Juan was then a pre-adolescent boy. He was shy and self-absorbed like all teenagers, but he even more so because of his Chorti identity. Crossing the 17 fords of that beautiful and noisy ravine, I would arrive at La Coroza. I was welcomed with a cup of coffee in Juan’s small house, with a plate of eggs, beans and tortillas. And that was all. I always arrived in the morning, around 9 am. I would carry out the activities of a pastoral visit: visiting the sick, meeting with the local church council where I would be advised of what had happened in the two months between one visit and the next. The last item to discuss was about sacraments, in case there were to be baptisms. Before celebrating mass I met with the youth group.

Although he was a pre-adolescent, Juan participated in the meeting. It was such a poor community that my visit was probably the only excuse for them kill a chicken. Most chickens were raised to sell or to nest in order to produce a new brood of chicks. Juan was one of the few boys who joined the conversation and he always caught my attention. When Sister Maria, a Spanish nun of the Daughters of Charity who came to Honduras to stay until her death in April 2006, accompanied me on the visit, she directed the youth meeting, and on our return – with me skipping stones and her on a mule – she always said to me: “that little boy is worth his weight, if we nurture him he will be a great and responsible man“. I was silent, but I remembered those words about Juan.

La Coroza razed to the ground

On one of my last visits to La Coroza, I spoke to Juan face to face: “What if you come to Tocoa to study? Sister Maria and I will support you“. As usual, Juan lowered his head. He half nodded without saying a word. On my return I spoke to Sister Maria and asked her to encourage Juan to come to Tocoa to study. On October 31 1993 tragedy struck as a result of one of the many tropical storms that hit the Honduran Atlantic coast and the community of La Coroza was swept away in a mudslide. It disappeared forever. Several people were buried, but Juan’s family was saved and had to migrate to nearby communities. Later the family moved to Tocoa, and Juan began his studies, first in the school via radio programs and then in the formal education system.

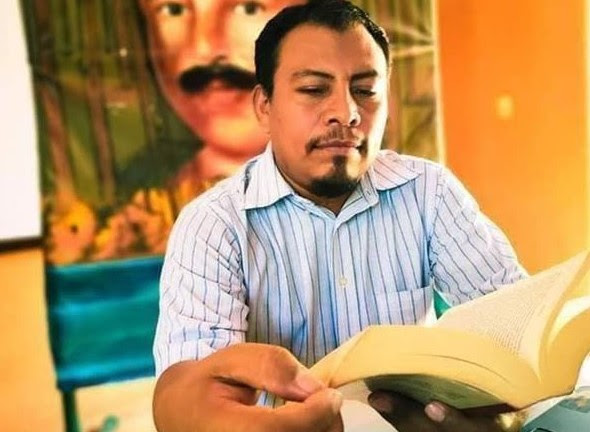

Juan, paradigm for new leadership

I left Tocoa in January 1997, and I did not meet Juan again until the beginning of the century, when he was already an educator and living in the Fabio Ochoa colony. He was involved in pastoral ministry in the parish of San Isidro Labrador de Tocoa and had all the years of this century to excel until he became a model of a new leadership. In an exemplary way Juan knew how to unite faith with justice, the social struggle with the political struggle, and the defence of human rights with the struggle to protect the rights of the common home. And he did it with his life, his daily work, his closeness to his wife and two daughters, with his testimony of life as a committed layman, with his words spoken with simplicity and clarity, with his written word, with the journey from poverty, as an authentic intellectual who never separated himself from his origins.

“For a Christian, no road is off-limits”. But for Juan they they did set up a roadblock

The last time I saw and heard him was on 7 September, the Saturday before his assassination, at a national ecclesial meeting for integral ecology. I listened when he said that for a Christian no path was off-limits to promote justice, dignity and the defence of the common home. No road. He said it forcefully. And I understood that he was saying it to all the people of the Church who were gathered in that room, including several priests and two bishops. And I understood that he was saying it to me, because he knew that I was not sure of the appropriateness of his participation as a candidate for mayor of Tocoa.

I knew he was saying it to me, because five years ago – in 2019 – he gathered his closest friends to tell us of his intention to run for mayor of Tocoa – where he was already an elected councillor. Then I told him that I did not agree, not because he was not valiente in the field of fighting for public office, but because he would be facing such great powers in the area, and with so little compensation, that in those conditions not only would he not be able to defeat them, not even with the strength he could muster with popular support, but his life would be in jeopardy “like a lamb to the slaughter”. “Juan” I said, raising my voice, “they will kill you. On that path neither the miners, nor the landowners, nor the merchants, nor the politicians will let you move forward. And neither will your own party LIBRE.”

“No road is off-limits”, he said, and I felt his words were meant to resonate with me. Our eyes met, and we both looked down. That’s when I remembered my words from 2019. And I said that in my consideration his involvement in the election campaign that was already underway in that same month of September was not opportune at that time. The wild beasts were loose, unruly and wounded. They were more dangerous than ever. I knew that this time Juan could win the votes to be the mayor of Tocoa and the elections at the end of November 2025. He had many opponents, especially the mayor of Tocoa, from his own party. Fúnez was not just an adversary, he was the enemy with a fortress strength among all the public and underground powers. And in the preliminary elections, this mayor, Adán Fúnez, would seek to destroy Juan in any way he could. But it was not just the mayor. He represented many organized forces of destruction and death.

No one with the power that perversely has invaded the Aguán would allow Juan López, a poor, indigenous, grassroots man whose firm and reassuring word could gently and convincingly reveal the truth to the communities, to beat them to the punch. It is all about power. But it was also a matter of honour. They could not allow “a commoner” to occupy the place that only their chosen ones could occupy. It was a political and economic issue, an issue of class struggle, and equally a racist and discrimination issue.

Then I turned my gaze to him. Juan already had his eyes busy at his computer. He was deep into his writing. And silently I repeated to myself what I had said out loud to him in 2019: “Juan, they are going to kill you”. That was Saturday September 7 in San Pedro Sula. Life went on with its busyness. Until Saturday 14 September, at 8.15 pm when my friend with hands trembling showed me the mobile phone and I heard from the caller that they were telling me, “Juan has been murdered“.

That’s how life goes, and that’s how it is to write chronicles of blood spilled for a love greater than saving oneself. That love for which Juan López was murdered. That love for which he wanted to give his life so that we might live following in his generous footsteps, now stained with his innocent blood.

By Ismael Moreno, SJ

Published on the Honduras – Country in Pain website